There is a long list of New Yorkers who have been devastated by the COVID-19 crisis: essential workers, the working poor, and parents struggling to juggle remote school with their own work, to name a few.

Yet often lost in the conversation is how the pandemic has impacted justice-involved individuals. Not only do those cycling in and out of jail face an extraordinary high-risk of contracting the virus as they sit in inhumane facilities where social distancing is impossible and access to health basics are scarce, the pathway to stability and success upon release has become even more daunting.

Jails are hotspots for COVID-19. At the height of the pandemic, Rikers Island had an infection rate that was approximately four to five times higher than city and state averages. We cannot let lack of testing stop our fellow New Yorkers from reuniting with friends and family or finding stable housing due to the fear of the disease, or worse, increased infection rates. Just one day without a place to stay can spell disaster and lead to homelessness.

The City needs to take action now to ensure the hundreds of people returning home from Rikers can get back on their feet. While the Mayor’s administration listed several positive steps in a City Council hearing last month to create a more unified reentry process, there are key issues we must act on now: providing COVID-19 testing and eliminating NYCHA’s permanent exclusion.

There are common-sense solutions will stem the tide of New York’s homelessness crisis and greatly improve the health, safety, and lives of countless New Yorkers.

Given the high-risk jails pose to community spread, it is imperative that justice-involved individuals are guaranteed testing before they leave. As we see an increase in density in jails, this infrastructure should mirror that of entry testing to ensure COVID-19 does not spread.

In addition to addressing private landlord discrimination, we must confront less-discussed discrimination in public housing: the NYCHA permanent exclusion.

This policy allows NYCHA to unilaterally decide whether someone with criminal history is “non-desirable,” thereby banning them from tenancy for as long as five years. Only after reapplying can former residents have the chance at having this status removed.

This unfair and unjust rule mirrors the racist and unequal treatment in our criminal legal system. We know that people of color in New York City are far more likely to get arrested than white residents. Rather than try and right the wrongs of the past, the NYCHA exclusion policy actively legitimizes this broken status quo.

NYCHA’s proposed changes to this rule offer an opportunity to create a public housing system that treats formerly incarcerated New Yorkers with the respect and dignity they deserve. We must eliminate this discriminatory policy once and for all.

These changes are no-brainers that do not require a meeting of the minds or time-consuming study. Time is of the essence during this pandemic.

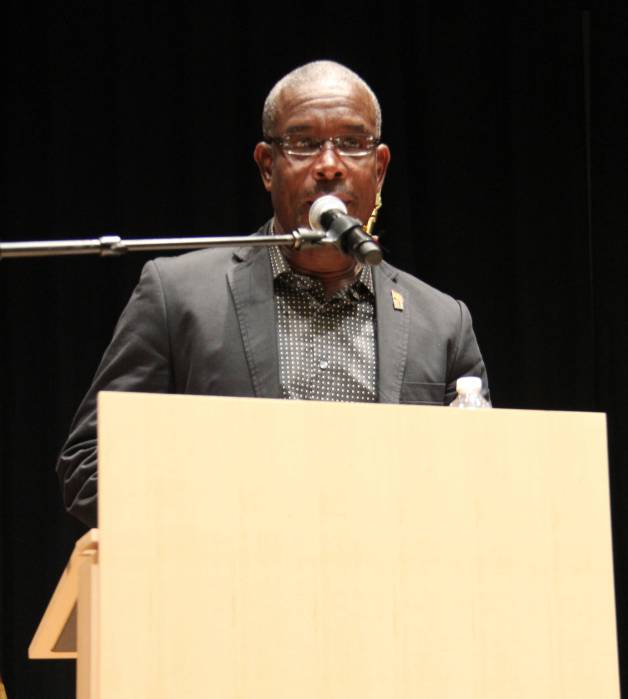

Council Member Keith Powers represents New York City’s District 4 in Manhattan. Rev. Kevin VanHook presides at Riverside Church in New York City.