In the 50th year of separation from government ending its position as the religious denomination that ruled Barbados, the Anglican Church is being given an ultimatum to alter practices and put a modern touch to rituals so it will embrace young people of this island – or face extinction.

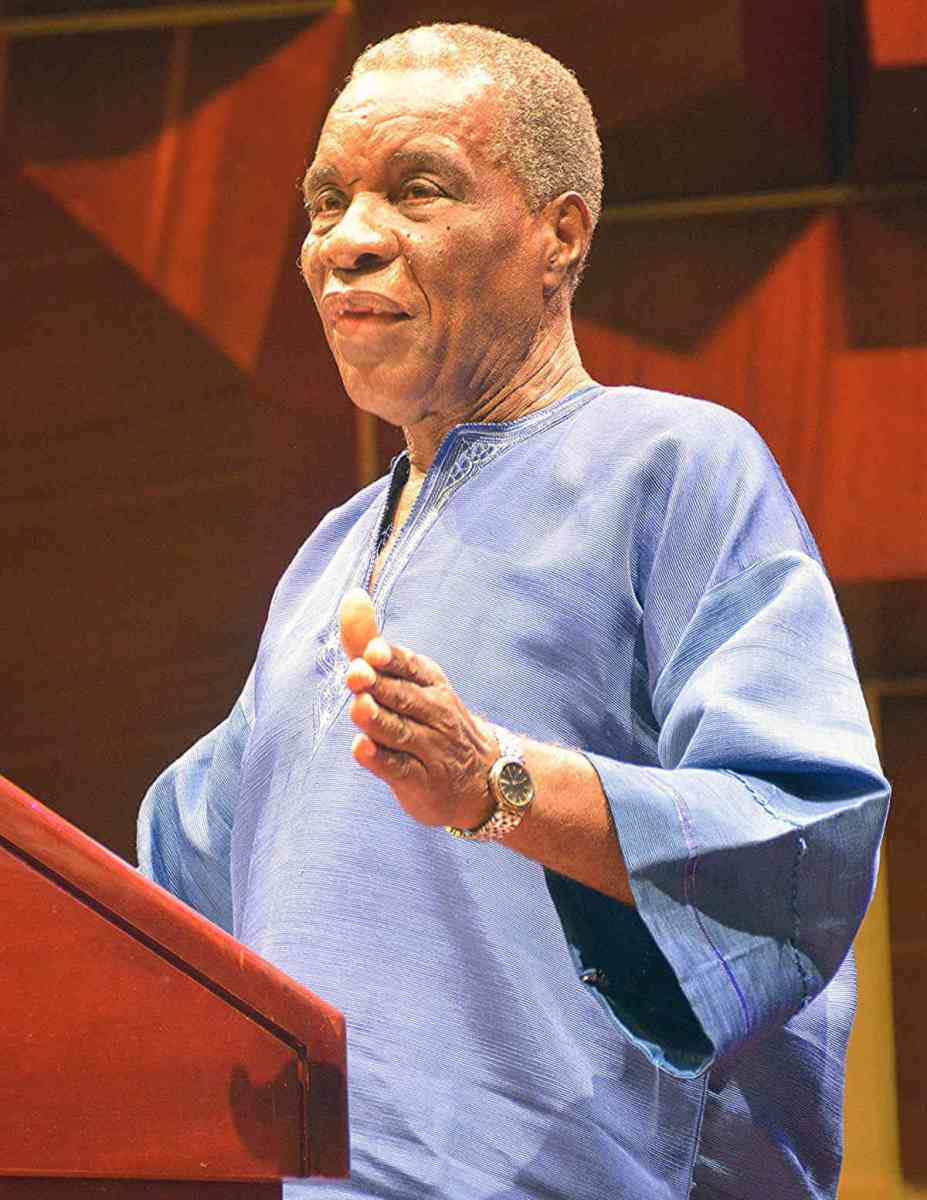

That demand has been made by one of the island’s foremost historians, Trevor Marshall, who sees Anglicanism at the crossroads where a wrong turn could lead to extermination of this religious sect that one year after settlement in 1627 began acting as the de facto government carving out and naming the island’s 11 parishes as they stand today.

The Anglican Church continued this domination of governance of Barbados with its clergy paid from the national treasury and assets maintained at the expense of the public purse until April 1, 1969 when an Act of Parliament severed government’s ties to the denomination.

This act came three years following the island’s political independence from Britain.

The law severed government’s ties to the church and passed on to the Anglicans responsibility for maintenance of its own buildings, payment of its clergy and management of all affairs.

It meant that the Anglican leader no longer held the title of bishop of Barbados, but only bishop of the church.

Marshall, who lectured history at the University of the West Indies and Barbados Community College, said that in the 50 years leading to the golden anniversary of dis-establishment of the Anglican Church in Barbados there were two notable changes: a movement towards gender balance to the extent that women are about to take over almost all major leadership positions; and a change in racial composition in the hierarchy reflecting Barbados’ predominant black population.

“We have 20 ladies in the Anglican Church who have assumed the position of leaders of parishes,” he said. “By 2029 it is likely that the cadre, the cabal, the group of ladies in charge of parishes will be about 50 percent of the Anglican Church.”

He reflected that not until 1993 did the Anglican Church in Barbados have a Black bishop, some 170 years since having a prelate appointed to the territory. He noted that the movement towards females taking up leadership positions was even slower and the furthest in that direction was what he sarcastically described as “a revolutionary step forward of appointing ladies as choir mistresses” in the 1950s.

“The notion of [women] ever becoming deacons, vicars, lay readers, cross carriers, altar servers, heads of choir, even priests, that was science fiction.”

Marshall said that full female leadership of the Anglican Church is long due because women comprise the majority of believers.

On the matter of the slow change of the Barbados Anglican Church to its leadership being representative of the black dominance of the membership, Marshall noted that the last of the England appointed bishops, was Bishop Hughes who left the island in 1951.

“Were Hughes to suddenly re-appear and see the Anglican Church he would be, not just perplexed, he would be non-plussed … because the Anglican Church in Barbados has not only emancipated itself from England. It has been blackened. It has been browned.”

The retired lecturer said, “when I was a little boy in St. John, every priest was white.”

“Every other Caribbean country had indigenised and had blackened the priesthood, by the time I went to Mona [UWI Campus] in 1968 Jamaica had black bishops.”

He said that coming from his Barbados experience, “I could not believe it …We thought that God anointed all white people to be bishops of Barbados and we did not see the possibility of a black person becoming bishop.”

“Every Caribbean had a black Bishop by the 1960s. We had to wait until 1993, 25 years.

“The revolution reached us 25 years after it started in the rest of the Caribbean.”

But with these two significant areas of progress in Barbados’s Anglican Church, Marshall said more is needed for this dominant religion on the island to retain its leadership position.

“You must change, adapt or die,” was his ominous warning.

“It is fundamental because if the church does not change it will not survive,” said the historian who boasts of his strong Anglican faith.

“If the church is only the church of the over 50s in terms of its literati … and its hymnal orientation, it will not survive.

“The church must find some way of dealing with the demands of the young people… there is a need in them for something bigger than we all had. My generation was satisfied with the lilting hymn songs.

“The children are not satisfied with that any longer.”